#Spring is on the way. Honest. And here's why... #ldnont

/April arrives next week, and this morning people living anywhere from Detroit to Toronto awoke to a dusting of snow and the promise of more to come this afternoon. Worse than the snow are the ongoing sub-freezing temperatures, which continue to stiff-arm the arrival of anything even resembling spring.

In most parts of the world, the changing of the seasons is a rhythm we expect and rely on in the same way we expect the sun to rise each morning. Our entire society is organized around the seasons, so when winter refuses to leave the stage for spring, we get grumpy. And not just because we’re still brushing snow off our windshields three months after Christmas.

Last week, some poor soul was trudging around our neighborhood trying to sign up homeowners for lawn maintenance this summer. That’s a tough sell when you can see his footprints in the snow, tracking from door to door. Sure, we know eventually we might need his services, but the idea of agreeing to spend money on that right now, with mounds of snow still dotting parking lots and cul-de-sacs everywhere, well, that’s a tough sell.

Perfect confluence of sun and snow Photo: John Barwell

Deep down, however, we know the next season will arrive. It may be later than average, it may be wetter or cooler or drier or warmer than we would like or than we think we remember compared to that one year when everything was absolutely perfect, but we never really doubt the next season will arrive. We’ve been conditioned to expect it; it’s happened every year of our lives. So that’s why it’s so amazing to think about everything that had to happen, millions of years ago, to establish season-friendly conditions.

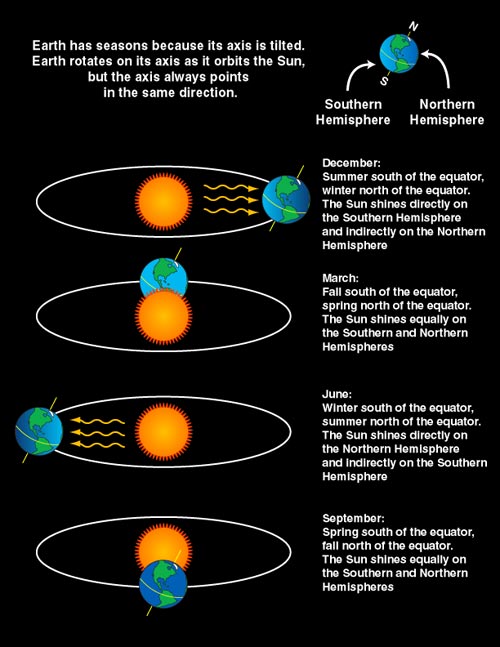

There are two factors that create seasons on any planet in our solar system – the shape of its orbit around the sun and the tilt of the planet on its own axis. On the Earth, it’s only the tilt that has any effect on our seasons. Our orbit is pretty close to a perfect circle, which means our distance from the sun varies only slightly during the year. To demonstrate how insignificant the change in distance really is, consider: Earth is closest to the sun during winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

Mars, by contrast, is 10 per cent closer to the sun during its summer than its winter. That makes for a serious change in climate. Good luck keeping your lawn watered during a Martian summer. The orbital effect is so dramatic that the atmospheric pressure on the planet is 25 per cent lower in the winter than the summer. That’ll cause some earaches.

It may feel as though we have large temperature swings on Earth, but they’re nothing compared to other planets that swing wildly closer and further from the sun. The thing that dictates our temperature changes, and thus our seasons, is the 23.5 degree tilt of the earth on its axis. The axis is imaginary, but the effect mostly certainly is not.

Think of the earth as a melon you’re considering buying at the local market – a melon that’s pretty much perfectly round. There isn’t really an axis running through it; you can turn the melon any which way and it’s still a sphere. But you know the seeds are running a certain way, and you cut it open so they run from top to bottom. The Earth’s axis is like those seeds, only they’re tilted 23.5 degrees. So what, you say?

That tilt wakes up hibernating animals each spring. It prompts migrating birds to begin their travels twice a year. It delivers the glorious oranges and reds of fall foliage. And it’s the reason we know the mounds of dirty, grey snow all around us will melt…eventually.

Millions of years ago, a big rock called Theia slammed into Earth. No one was around at the time, so there aren’t any selfies of people standing near the impact zone. It caused quite a mess, lots of dust and such, the same kind of thing we think spelled the end for the dinosaurs much later. Theia, we think, knocked Earth from rotating straight up and down – along the line of seeds in that melon – to rotating on its current tilt. And ever since then, parts of Earth get more direct sunlight at different times of year. When the Northern Hemisphere is facing the sun, it’s summer up there and winter down under mate.

Somehow, among all the billions of planets and stars and dark matter and space dust whizzing through a universe so large it’s nearly impossible to comprehend, we live on a planet tilted at just the proper angle to deliver the same four seasons year after year after year. Somehow, our orbit and distance from the sun are set just right to give us consistent temperatures from season to season. Climate change may be inching those averages up a tiny bit, but stop and think how amazing it is that our summer temperatures this year will be within a few degrees of what they were 10 years ago, 100 years ago, 1,000 years ago and beyond.

This summer may be hotter than average, by what, one degree? On Venus, the daily temperatures fluctuate by more than 600 degrees Kelvin. You’d better take a coat if you go out at night. It’s gonna get chilly.

It’s one week until April, and grumble as we might, those of us in this part of the world know spring will arrive in the next few weeks. We never really doubt it will happen; we just complain about the timing. Instead, consider how amazing it is that it returns every year in the same form with the same collection of wonderful sights and smells, as it has for tens of thousands of years.

It’s worth pondering while you sip a hot chocolate in mid-April, wondering when your tulips will finally poke their heads through the frozen tundra that is your garden.